Dr Nae Hee Han, worldsteel Director, Economic Studies and Statistics

17 April 2019

Our April 2018 Short Range Outlook was based on a rosy picture of the global economic environment, which turned somewhat sour in the third quarter of 2018.

Two factors contributed to the worsening of the economic environment. First, the global economic cycle peaked during the course of 2018. Second, uncertainties have escalated with trade wars leading to financial market volatilities. Added to this, the world has been nervous about China’s slowdown.

As a result, global economic institutions like the IMF and the OECD have continuously been revising downward their economic forecasts for 2018 and 2019.

As we move into 2019, the risks have not subsided, uncertainties remain elevated and trade tensions are still on top of the list along with China’s slowdown.

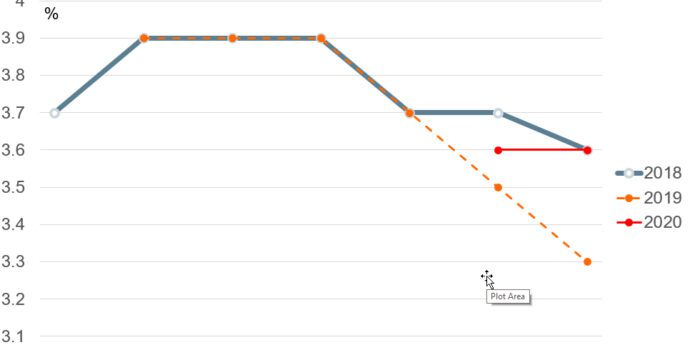

The graph below tracks the changes in IMF Global GDP forecasts from October 2017 to 2020. We can see that global GDP growth forecasts for 2018 and 2019 have been revised downward continuously since our October 2018 SRO reflecting the above factors.

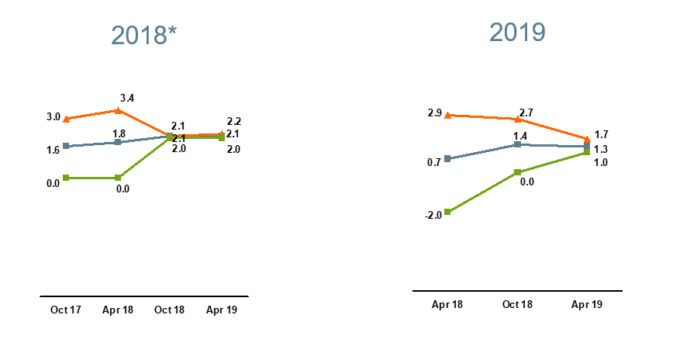

With this background, the results of our 2019 SRO come as no surprise. Our forecasts for growth of global steel demand in 2018 and 2019 have remained surprisingly stable with virtually no revisions since the April 2018 SRO, despite a rather dramatic turnaround in the economic sentiment mentioned above.

This is rather unexpected. Usually, steel demand fluctuates considerably around business cycles and is sensitive to business confidence, but it does not seem to be the case this time.

However, when we look at the details of revisions, we do see some upward and downward revisions. China’s steel demand forecast for 2019 was revised up by 1 percentage point on the account of stimulus measures, which was offset by a 1 percentage point downward revisions in the rest of the world.

But the downward revisions in the rest of the world come mostly from Turkey and the Middle East, which is accountable to region specific factors (i.e. currency crisis and oil price, respectively).

So, all in all, steel demand stood resilient to the economic downturn in many parts of the world. Later on in 2020, the growth is expected to accelerate in most emerging economies.

So, it is true that due to China’s structural transformation, the global steel industry has moved to a slower growth pace, but the global steel industry can still count on the emerging economies to continue to drive growth in steel demand even in difficult times – particularly India and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).