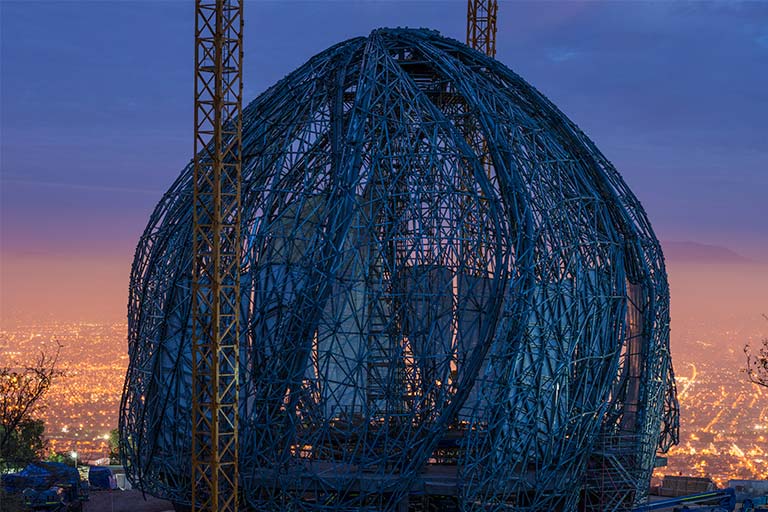

The acclaimed Bahá’í Temple of South America is the result of 14 years of experimentation, challenges and complex engineering

Hariri Pontarini Architects’ recently completed Bahá’í Temple is a sculptural, domed structure, located in the foothills of the Andes in Chile, which welcomes people of all faiths and cultures from around the world.

The Temple was first commissioned by the Bahá’í Community back in 2003, following a global design competition. When the selection panel was presented with Canadian architect Siamak Hariri’s organic, curved design, the decision was unanimous.

Hariri’s nine-sided steel superstructure features nine bronze doors – symbolically welcoming people from all directions – and is the last of eight continental Bahá’í Temples to be constructed as part of a portfolio of sacred architecture.

Light is of great importance to the Bahá’í faith, and the design was developed through hand sketches, models and digital technology, with the aim of producing a universally attractive form that would capture light.

The first challenge involved finding a suitable plot of land. Ultimately, a bare, high hill was purchased, which is located just 20 minutes from central Santiago, the capital of Chile. “We conducted feasibility studies on several pieces of land before settling on a ten-hectare former golf course,” explains Doron Meinhard, project manager and associate-in-charge.

“When people walked inside they fell silent, and many were moved to tears. Then a choir started singing, and at that moment the Temple went from being a construction project to a spiritual place.”

Doron Meinhard

“Another challenge was the budget, which had been established back in in 2006,” Doron continues. More than $30-million was raised from Bahá’í Community donations, and this budget was somehow maintained despite the many years of research, development and engineering that it took to complete the Temple.

What appears as a graceful, ethereal form, with its twisting, wing-like elements, is built in an active seismic zone and required innovative engineering solutions to ensure it will withstand potential earth tremors, as well as diverse weather conditions, for at least the next 400 years.

A carefully detailed steel superstructure was built on a foundation ring, which bears onto seismic isolation pads to accommodate ground movement. Nine identical wings are separated by crescent-shaped windows, and taper as they rise up to meet in a spiral at the apex.

Each wing is made from 850 slim-profile lengths of steel and nodal connections, similar to the veins of a leaf, which form a frame that supports more than 450 tonnes of bespoke cladding; translucent marble for the inner and cast-glass panels for the exterior.

“The nodes are like the DNA of the Temple,” says Meinhard. “The frame was redesigned several times, and more intricate faceted nodes were needed to allow the cladding to follow the shape of the frame closely and without gaps.”

Made in Germany by Gartner Steel and Glass GmbH, who are well known for their complex 3D structures, the frame was constructed using CNC plasma cutting and 5-axis CNC milling machines, with the ability to move a part or a tool on five different axes simultaneously.

What appears as a graceful, ethereal form, with its twisting, wing-like elements, is built in an active seismic zone and required innovative engineering solutions…

“Trials showed too much variability using typical robotic milling machines, but this mechanism reduces vibration, making results far more precise,” Meinhard explains. “Only one company in the world could do this for us.”

Translucent Portuguese marble was chosen to line the interior of the frame, with 1,129 pieces of flat and curved glass forming the outer-torqued wings – allowing light to enter during the day and illuminating the building from within at night.

“We had a lot of failures, and all nine pieces of curved glass for the large-scale model broke in transit,” says Meinhard. “It was a huge concern, but new technology was developed specifically for this project.”

The glass wings frame an open space, which can accommodate up to 600 people on curved walnut and leather seating. Looking up to the central oculus, visitors can experience the changes in light – which are particularly marked at sunset when the dome is coloured in vivid silver, ochre and purple hues.

Work continued on the building and on landscaping the site until just before the award-winning temple was due to open its doors in October 2016.

“It was a really beautiful day, and the quality of light was amazing,” Meinhard recalls. “When people walked inside they fell silent, and many were moved to tears. Then a choir started singing, and at that moment the Temple went from being a construction project to a spiritual place. After so many years working there we could finally hand over the building to the community.”

Images: Hariri Pontarini Architects, Guy Wenborne